Lab-produced antibody, new hope in HIV fight

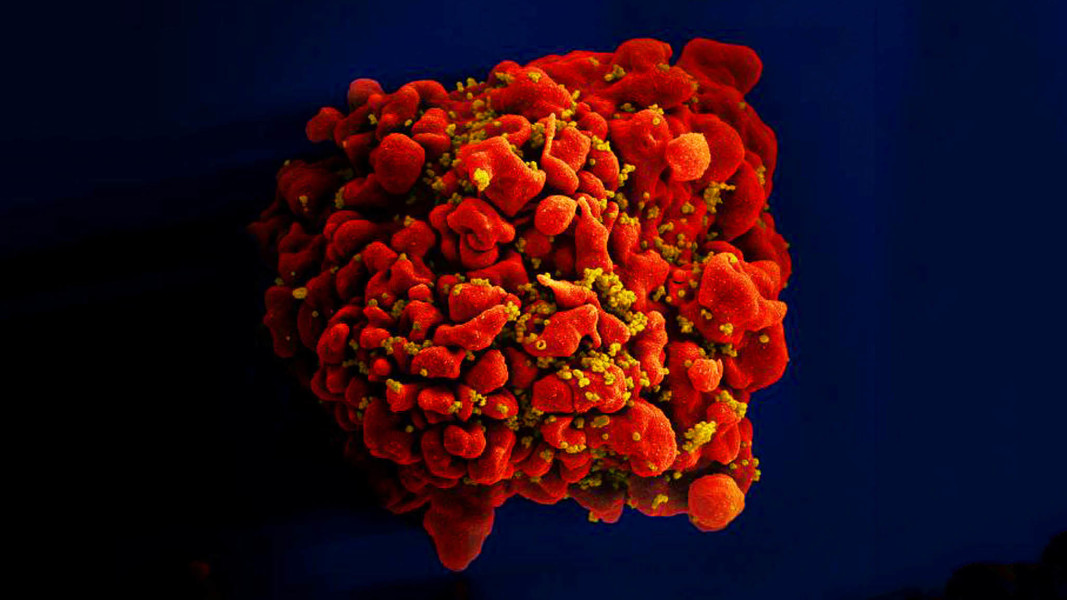

A large international study has shown that it is possible to prevent some HIV infections with infusions of a particularly potent protein known as a broadly neutralizing antibody, but it will likely take a combination of different and more potent proteins to block all strains of the shape-shifting virus.

This follows promising results that show injecting broad neutralising antibodies (bNabs) in HIV-negative people has the potential to kill the human immunodeficiency virus before it infects the cells.

On Tuesday, two proof-of-concept studies that tested an experimental antibody, VRC01, against HIV on more than 4,600 people raised the hopes of researchers after it achieved 75% protection in study participants during the 20-month study period.

The AMP results include data from HVTN 704/HPTN 085 which enrolled about 2,700 men and transgender people who have sex with men in the US, Brazil and Peru, and HVTN 703/HPTN 081, which enrolled about 1,900 women from Africa.

While traditionally vaccines are given to stimulate the immune system to make antibodies that can neutralise infectious viruses, with this approach, known as passive immunisation, participants were infused with the potent antibody at eight-week intervals over 80 weeks. AMP participants who received the antibody were 75% less likely to become infected, but the antibody was only effective against two strains of HIV, subtype C in Africa and subtype B in the other participating countries.

Antibody infusions prevent acquisition of some HIV strains, NIH studies find https://t.co/KVkLz6qrE5

— Markian Hawryluk (@MarkianHawryluk) January 26, 2021

Overall its prevention efficacy was 26.6% among men and transgender people in the Americas, and only 8.8% among African women.

However, in the 30% of cases where people were exposed to VRC01-sensitive strains, the rate of HIV acquisition was 0.20 per 100 person-years among people who received the bnAb, compared to 0.86 per 100 person-years among those who received the placebo. That means that, in this minority of participants, VRC01 was associated with a 75% drop in new infections.

For comparison, daily oral Truvada or Descovy for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) are around 99% effective when used consistently, and once-monthly cabotegravir injections may be even more effective in real-world use.

VRC01 was well tolerated in both trials. No safety concerns were identified, and adherence was high, Corey reported.

Though not as successful as hoped in these studies, the results are a promising first step, according to Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) at the National Institutes of Health, which sponsored the trials.

“These findings establish the concept that passive administration of a broadly neutralizing antibody can prevent acquisition of susceptible HIV strains,” he said in a press release. “Insights gleaned from the AMP studies lay the foundation for future development of long-acting antibody-based HIV prevention tools and, ultimately, a vaccine.”

Corey said that he considers the study a success because the researchers were able to identify biomarkers and develop a laboratory test to predict whether an antibody would work against different strains of HIV and how much is needed for protection, providing tools to move the field forward.

Since the AMP studies began, scientists have made progress on optimizing bNAbs to increase the number of HIV strains they can block, how strongly they bind to the virus, how long they last in the body and how efficiently they trigger an immune response against the virus itself and against HIV-infected cells. Potentially, these optimized bNAbs could be combined to develop a highly effective HIV prevention method, according to NIAID.

Corey noted that antibodies are already in use for many diseases, including for prevention and treatment of COVID-19. He added that it might be possible to administer antibodies by subcutaneous or intramuscular injection rather than IV infusion, and the cost is dropping. “I do think they will be economically feasible if they have high efficacy,” he said.