Is electricity the new medicine?

Could a tiny electronic device treat some diseases more safely and effectively than pharmaceutical medicines?

For Kelly Owens, the answer was clear. She spent more than a decade suffering from Crohn’s disease, a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that left her with severe arthritis in her joints. The pain forced her to use a cane, sometimes a wheelchair. She tried more than 20 medications and racked up more than $1 million in medical bills, but her condition didn’t improve.

A physician told Owens and her husband that they shouldn’t have children, and that she’d have to take steroids for life.

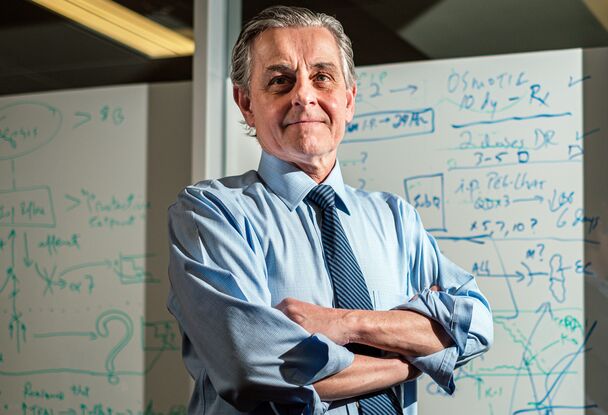

Then Owens turned to bioelectronic medicine. She reached out to Dr. Kevin Tracey, a pioneer in the field and president and CEO of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in New York. Soon after, Owens and her husband moved to Amsterdam to participate in a clinical trial involving a relatively new bioelectronic approach to treat inflammation.

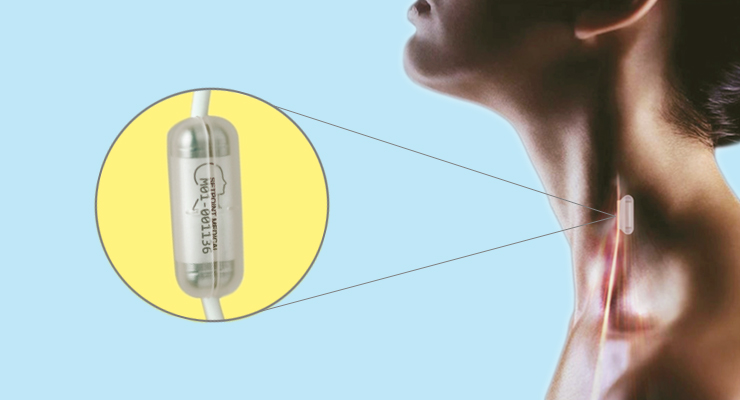

Doctors implanted a small electronic device in her chest that stimulated her vagus nerve, the body’s longest cranial nerve. After two weeks, Owens didn’t need the cane or wheelchair. Soon she was jogging on a treadmill.

A growing body of research within bioelectronic medicine shows it’s possible to treat diseases by manipulating the nervous system. The field is essentially a fusion of neuroscience, molecular biology and neurotechnology. Dr. Tracey and his colleagues think the field may someday replace or supplement many pharmaceutical drugs used to treat major diseases, including cancer and Alzheimer’s.

But how? The answer centers on how the nervous system controls molecular processes in the body.

You accidentally place your hand on a hot stove. Almost instantaneously, your hand withdraws.

What triggered your hand to move? The answer is not that you consciously decided the stove was hot and you should move your hand. Rather, it was a reflex: Skin receptors on your hand sent nerve impulses to the spinal cord, which ultimately sent back motor neurons that caused your hand to move away. This all occurred before your “conscious brain” realized what happened.

Similarly, the nervous system has reflexes that protect individual cells in the body.

“The nervous system evolved because we need to respond to stimuli in the environment,” said Dr. Tracey. “Neural signals don’t come from the brain down first. Instead, when something happens in the environment, our peripheral nervous system senses it and sends a signal to the central nervous system, which comprises the brain and spinal cord. And then the nervous system responds to correct the problem.”

So, what if scientists could “hack” into the nervous system, manipulating the electrical activity in the nervous system to control molecular processes and produce desirable outcomes? That’s the chief goal of bioelectronic medicine.

“There are billions of neurons in the body that interact with almost every cell in the body, and at each of those nerve endings, molecular signals control molecular mechanisms that can be defined and mapped, and potentially put under control,” Dr. Tracey said in a TED Talk.

“Many of these mechanisms are also involved in important diseases, like cancer, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, hypertension and shock. It’s very plausible that finding neural signals to control those mechanisms will hold promises for devices replacing some of today’s medication for those diseases.”

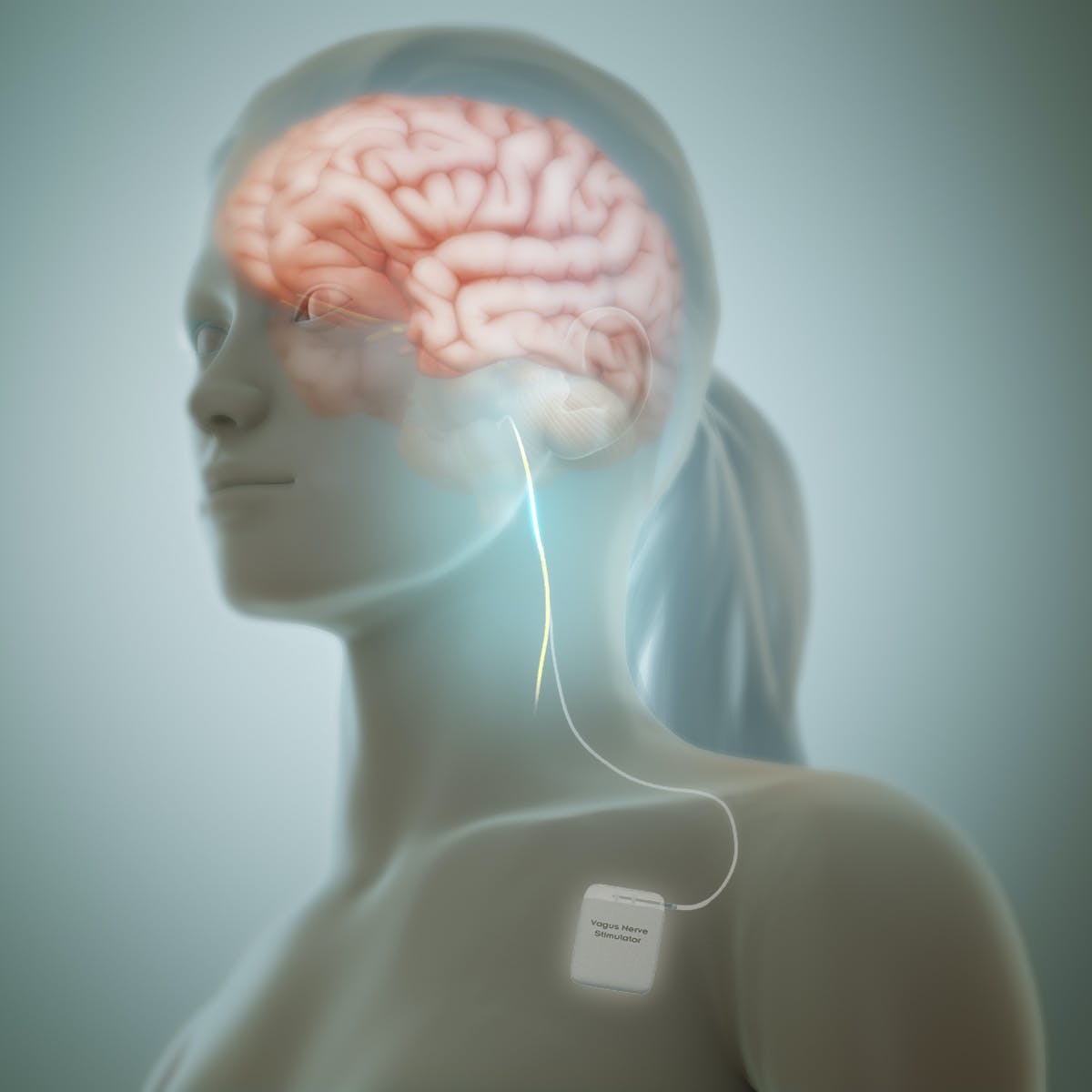

How can scientists hack the nervous system? For years, researchers in the field of bioelectronic medicine have zeroed in on the longest cranial nerve in the body: the vagus nerve.

The vagus nerve (“vagus” meaning “wandering” in Latin) comprises two nerve branches that stretch from the brainstem down to the chest and abdomen, where nerve fibers connect to organs. Electrical signals constantly travel up and down the vagus nerve, facilitating communication between the brain and other parts of the body.

One aspect of this back-and-forth communication is inflammation. When the immune system detects injury or attack, it automatically triggers an inflammatory response, which helps heal injuries and fend off invaders. But when not deployed properly, inflammation can become excessive, exacerbating the original problem and potentially contributing to diseases.

In 2002, Dr. Tracey and his colleagues discovered that the nervous system plays a key role in monitoring and modifying inflammation. This occurs through a process called the inflammatory reflex. In simple terms, it works like this: When the nervous system detects inflammatory stimuli, it reflexively (and subconsciously) deploys electrical signals through the vagus nerve that trigger anti-inflammatory molecular processes.

In rodent experiments, Dr. Tracey and his colleagues observed that electrical signals traveling through the vagus nerve control TNF, a protein that, in excess, causes inflammation. These electrical signals travel through the vagus nerve to the spleen. There, electrical signals are converted to chemical signals, triggering a molecular process that ultimately makes TNF, which exacerbates conditions like rheumatoid arthritis.

The incredible chain reaction of the inflammatory reflex was observed by Dr. Tracey and his colleagues in greater detail through rodent experiments. When inflammatory stimuli are detected, the nervous system sends electrical signals that travel through the vagus nerve to the spleen. There, the electrical signals are converted to chemical signals, which trigger the spleen to create a white blood cell called a T cell, which then creates a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine. The acetylcholine interacts with macrophages, which are a specific type of white blood cell that creates TNF, a protein that, in excess, causes inflammation. At that point, the acetylcholine triggers the macrophages to stop overproducing TNF – or inflammation.

Experiments showed that when a specific part of the body is inflamed, specific fibers within the vagus nerve start firing. Dr. Tracey and his colleagues were able to map these relationships. More importantly, they were able to stimulate specific parts of the vagus nerve to “shut off” inflammation.

What’s more, clinical trials show that vagus nerve stimulation not only “shuts off” inflammation, but also triggers the production of cells that promote healing.

“In animal experiments, we understand how this works,” Dr. Tracey said. “And now we have clinical trials showing that the human response is what’s predicted by the lab experiments. Many scientific thresholds have been crossed in the clinic and the lab. We’re literally at the point of regulatory steps and stages, and then marketing and distribution before this idea takes off.”