From Basel to Beeple: How will the art world fare post-pandemic?

The hubbub that descends each summer on a sleek exhibition hall in Basel, where collectors snap up art and hunt for hot-ticket new talent, is likely to be replaced this year by lines of socially distanced Swiss waiting for COVID-19 vaccines.

The Herzog & de Meuron building usually hosts one of the world’s biggest art fairs in June, but last year’s event was cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic and this year’s has been moved to September. The adjoining congress centre, meanwhile, has been turned into a vaccination hub.

The art world is reeling from the impact of lockdowns, travel bans and social distancing, and fairs like Art Basel suffered more than most. The business of buying and selling art is having to adapt to limit the damage.

Global art sales fell 22 percent in 2020 to $50.1bn, UBS and Art Basel’s Global Art Market Report published on Tuesday showed, the steepest market drop since the financial crisis of 2007-2008.

But the picture was uneven, as buying by the ultra-wealthy, notably from Asia, held up.

In contrast to the 2007-2009 financial crisis, when many of the world’s rich lost money, the super-rich have become richer during the pandemic as financial stimulus and volatile markets served to increase their fortunes.

Big auction houses, led by Sotheby’s and Christie’s, were already used to telephone bidding and online sales, and so could pivot relatively easily to appeal to cash-rich clients.

Both reported an overall dip but saw record online activity and resilience among Asian buyers, while pre-pandemic trends of interest in Black, female and living artists were reinforced.

This year, they hope to build on that, capitalising on an influx of young collectors who have found the online world more accessible than old-style auction rooms, and as more traditional buyers yearn to return to the real world.

“There is enormous pent-up demand for experiences and even spending, once there’s a bit more stability and predictability,” Sotheby’s Chief Executive Charles Stewart told Reuters news agency.

“We have the potential for just the biggest boom for a period of time, assuming that we get to a place where people are comfortable leaving their house.”

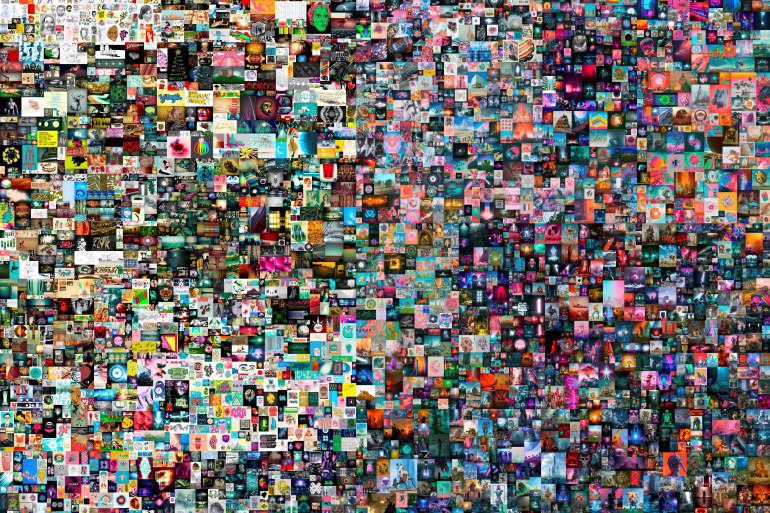

For Christie’s, 2021 has seen spectacular confirmation of the potential to create wealth from the virtual world as it hosted a record-breaking $70m digital artwork sale this month.

In an online auction held over 14 days, bids on the work by US artist Beeple started at $100 and accelerated dramatically, with 22 million visitors tuning in for the final minutes of bidding.

Christie’s plans to follow up on the success with further sales of non-fungible tokens (NFTs), or artworks that exist only in digital form.

More people appear to be willing to purchase artworks online without seeing the real thing first.

“What we have observed is the simple behavioural truth that collectors are more willing than ever before to buy from an image,” said Rachel Lehmann, co-founder of Lehmann Maupin, which has galleries around the world.

But she added that the digital space presented a challenge for artists and artworks that don’t translate well into an online image.

Winner takes all

For German artist ANTOINETTE, lockdown was not all bad: the cancellation of public events allowed her an extended stay in the east German castle of Merseburg, where she was working.

Using only pencils, she is creating intricate drawings on five-metre-high panels that form part of a multi-year project on European cultural identity entitled “ALTAR of Europe”.

Socially-distanced locals can watch her work through the windows, and ANTOINETTE said they had become her network.

“I’ve come to feel like a part of the community,” the artist told Reuters news agency.

But if she is fulfilled artistically, financially her situation is perilous, as commissions such as portraits have dried up during the pandemic.

Smaller galleries are also struggling, experts say, because the pandemic has accelerated the concentration of the art world into fewer hands – very wealthy buyers and high-profile and established sellers.

“Compared to the last recession, when everybody’s wealth went down, in this one billionaire wealth has really risen,” art economist Clare McAndrew, who authored the Art Market report, said.

“These things are good for art sales … But it does bring us back to our old problem of the infrastructure being very top heavy and kind of winner takes all.”

The UBS and Art Basel report found fairs accounted for 43 percent of art dealers’ sales in 2019 but only 22 percent in 2020, just under half of which were generated by digital events.

“The digital world is concentrating buying on what is fashionable [on social media] and through the big galleries that employ more than 100 people,” said James Mayor, who has run the Mayor Gallery in London since taking it over from his father in 1973.

Although he always attended Art Basel, he has avoided its digital offerings, which he says are no substitute for the real-life event. Some others agree.

“So far, digital formats have not replaced this as we benefit from face-to-face interaction and the atmosphere of a physical fair,” Stefan von Bartha, director at Basel-based gallery von Bartha, told Reuters news.

It is not just galleries that suffer.

During a normal year, Art Basel’s nearly 100,000 visitors to the city help boost hotel-room occupancy to almost full capacity during the first four days of the fair, or by some 35 percent to 60 percent over average levels over the week, Basel’s tourism office said.

Soul searching

Galleries and advisers interviewed by Reuters news anticipated a recovery in demand for fairs and art tourism post-pandemic.

Art Basel has scheduled a fair in Hong Kong for late May. Other major fairs, including TEFAF and Frieze, have said they expect to proceed with live fairs in some format later this year, complemented by digital participation.

But even before the COVID-19 crisis, some said there were too many fairs, and galleries and collectors say they will be more selective, sticking to the more local focus they have experienced over the last year.

In Hong Kong, galleries report strong business as China made an early recovery from the pandemic and the appetite for contemporary Chinese art grows.

“People have become very used to the extravagance of big fairs and big biennales celebrated in so many major cities,” Leo Xu, senior director at David Zwirner Hong Kong, said. “Honestly, I don’t miss that.”

The gallery, one of Zwirner’s six international locations, managed to increase sales in 2020, Xu said, primarily through outreach to wealthy, tech-savvy Chinese.

Also in Hong Kong, the Villepin gallery, run by former French Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin and his son Arthur, opened in March last year at the height of pandemic lockdown and said it had done “very well”.

In New York, gallery owners said there were positives, including a much-needed reassessment that might mean peripheral art fairs disappear, while Art Basel will almost certainly bounce back.

Sean Kelly, who runs a contemporary art gallery in New York, said the loss of art fair revenues has been offset by cost savings from not attending.

“We have to start thinking about the cost of the art fairs and I don’t mean the financial cost. I mean the physical and environmental cost,” he said.